Rate Shocks and How to Invest in a Bear Market

September 5, 2022

Heading lower again. What can investors do?

As I expected – and wrote about in previous editions of Big Money – US equities markets are headed back towards bear territory again.

Unsurprisingly, they will take the rest of the Developed Markets down with them. Further, there is no mark-to-market refuge in fixed income either, with global bonds now entering bear market territory too.

As bad as investors might think it is now, the outlook is for worse to come. I see Developed Market stocks going lower and bonds being hit by wider credit spreads and eventually higher levels of defaults.

So, there is little diversification or refuge offered by corporate credits or even government bonds in a multi-asset portfolio.

Your classic 50-50 “balanced portfolio” in Developed Market stocks and bonds would now look like an equal weighting in misery.

The obvious strategy flowing from my bearish views from Q1 2022 would have been to short equities, and I think it remains a valid one.

I do recognize, of course, this is a high-risk strategy. An alternative would have been long-short trades – long value stocks paired with shorts on growth stocks.

Stock risk from September seasonality

US stocks had another bad week, with the S&P 500 Index down 3.3%. It is now only 1.4% away from the 20% decline mark that puts it in “bear market” territory.

After heavy sell-offs, such as those of the past two weeks, there could be a bit of a fightback around the current level of 3,924.

This approximates the convergence of a horizontal support region around 3,900 and the 23.6% Fibonacci retracement of the January to June decline, which is located at 3,916.

But seasonality will be working against the sustainability of any rebound at these levels. According to Bloomberg, citing CFRA Research data, September is the worst month for the S&P 500’s average performance since 1945.

Meanwhile, October is the worst month for drawdowns. Leaving aside the historical statistics, the big dampener remains concern over US interest rates.

The US jobs market is cooling a bit off from red-hot levels, but not enough to cause the US Federal Reserve (Fed) to back off on rate hikes.

Dovish Fed on August jobs data?

The Fed Funds futures market interpreted August jobs data as giving the Fed some room for flexibility on rates, probably because of the rises in the labour force participation rate and the unemployment rate.

The probabilities of a 50-basis point (bp) rate hike in September went up from 25% to 43% on the jobs data. The odds of a 75-bp rate hike went down from 75% to 57%.

The Fed Funds futures market may indeed be right about the Fed going for 50bp in September instead of 75bp. But looking a bit further out, I think the Fed is far from done with rate hikes.

Indeed, the collection of data last week might be suggesting to the Fed it has a window of opportunity to crush inflation without socially painful/politically unacceptable levels of unemployment. But that window is not unlimited.

Total non-farm payrolls gained another 315,000 in August to 152.74 million, surpassing for the first time the pre-pandemic high of 152.50 million.

On a year-on-year basis, non-farm payrolls are up 4%. For historical perspective, the US recessions of 2007-2009 and 2001 started when non-farm payrolls growth fell to around 0.8% year-on-year (y/y).

The signs of cooling were to the found in the rise in the unemployment rate amid a rising labour force participation rate, which rose a bit from 62.1% to 62.4%.

How much time does the Fed have to crush inflation?

The US unemployment rate rose from 3.5% in July to 3.7% in August. This is important because it is one of those possible hints of how much time the Fed has before the US enters a recession.

Before the recession that started December 2007, US unemployment bottomed and started turning up in fits and starts from November 2006.

In a similar manner, before the March 2001 recession, US unemployment bottomed in April 2000.

Before the July 1990 recession, the unemployment rate bottomed in March 1989. For the double recessions from 1980-1982 which started January 1980, US unemployment bottomed in May 1979.

I don’t take into account the sudden-stop, pandemic recession of February-April 2020 for an obvious reason: There was no build-up to it.

So, taking other recessions going back to 1980, the lag between a bottoming of US unemployment to a recession ranges from 8-13 months.

The simple average was 10.7 months. As is the standard disclaimer – borrowed from Mark Twain – history doesn’t have to repeat, but it often rhymes.

And an important assumption is that unemployment this time around has bottomed at 3.5%.

Another marker might be found in the so-called “Sahm Rule Recession Indicator” (named after economist Claudia Sahmn).

This predicts the start of a recession when the three-month moving average of the US unemployment rate rises by 0.50 percentage points, or more, relative to its low during the previous 12 months.

The Sahm indicator is still at a benign 0.03%. In the lead up to the 1980 recession, it took 8 months to get from 0.03% to a recession.

Before the 2001 recession, it also took 8 months. In 2007, it took 9 months to go from 0.03% to a recession.

To repeat, this is not science, but a “gut feel” based on historical precedence: The Fed has 8-12 months before a recession becomes a serious risk.

It is noteworthy that average hourly earnings inflation for August eased slightly on a month-on-month (m/m) basis but remained stubborn at 5.2% y/y, where it has been since June.

Clock is ticking for Fed to beat inflation

So, it would seem sensible for the Fed to want to crush inflation within the next 8-12 months.

If it is half-hearted in this endeavour, it risks a recession anyway through inflation crushing consumer spending power and sentiment.

But by then, inflation could be much higher and it would have ultra-low real rates to boot. That’s the stagflation nightmare.

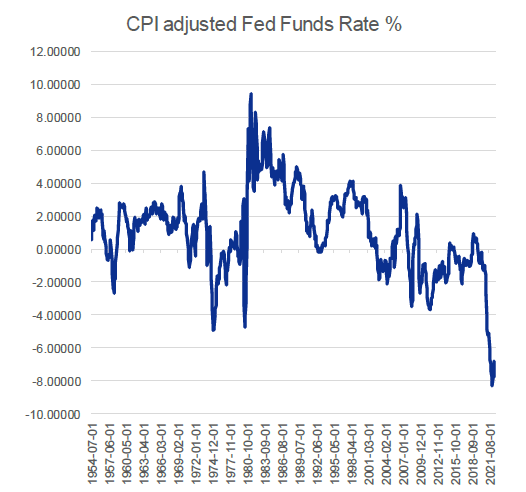

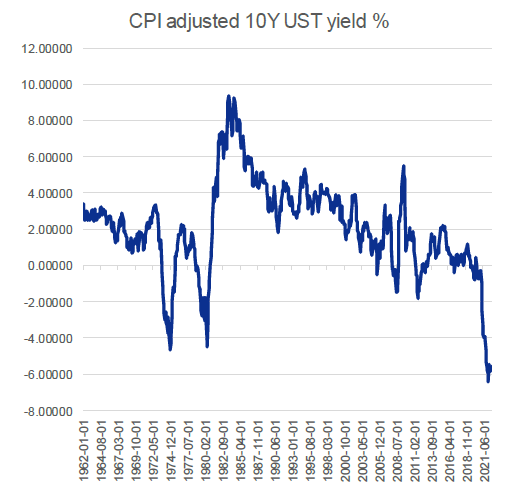

To show how shockingly behind the curve the Fed is in handling the inflation crisis, have a look at these two charts below; showing the real Fed effective rate (adjusted for the y/y all-items CPI rate) and the real 10-year US Treasury yield.

Both are in deeper negative territory than even the worst levels during 1970-1981.

Sources: CGS-CIMB Research, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

Elsewhere, the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index, which is around 40% weighted in US assets, is now down over 20% from its January 2021 peak.

That’s the worst drawdown since the inception of the index in 1990.

So, from a multi-asset perspective, there is not much separating US equities and US corporate credits’ performance for the year-to-date.

A 50-50 portfolio of US equities and credits is now a case of equal weighting in misery. While US Treasuries haven’t performed as badly, there is nothing good about being down 10% year-to-date either.

Here’s why the situation can only get worse

This scenario is unlikely to get better either, as the Fed trades off economic growth for lower inflation.

The ICE BofA BBB corporate credit spread is currently around 188 bps. If the US is going into a recession, which I think it is, a surge towards 350-400 bps is possible.

That is where they went following the 2001 and 2020 recessions. I am not considering the almost 800-bp horror in 2008 because that involved systemic risk in the banking industry caused by the collapse of Bear Sterns and Lehman Brothers.

It’s not that it cannot happen but I will consider that an outlier possibility. Note also that the current credit default rate is only a tad above 0%.

But past recessions have been followed by surges in the default rate to between 5% and 16%. I think the market is still far too complacent.

Say Boon Lim

Say Boon Lim is CGS-CIMB's Melbourne-based Chief Investment Strategist. Over his 40-year career, he has worked in financial media, and banking and finance. Among other things, he has served as Chief Investment Officer for DBS Bank and Chief Investment Strategist for Standard Chartered Bank.

Say Boon has two passions - markets and martial arts. He has trained in Wing Chun Kung Fu and holds black belts in Shitoryu Karate and Shukokai Karate. Oh, and he loves a beer!